Health equity in cancer care means everyone, no matter their social determinants of health, has the same opportunity to prevent, detect and treat cancer. Unfortunately, this is far from the reality today, but there are some ways you can address the underlying factors contributing to disparities and improve health equity at your own practice.

Boost health literacy

Due to differing educations and home lives, not everyone has the same understanding of cancer and how to handle a diagnosis, manage side effects and find support resources. You can help bridge the knowledge gap with education in your waiting room and exam room.

Showcase relevant health information geared toward patients, caregivers and survivors while they wait. This can be anything from preventive screenings and health content to helpful resources that reduce barriers to healthcare access. To be the most effective, the content you show should be actionable, use plain language and be relatable. Make sure to have education for patients at different stages of treatment and of different demographics and backgrounds.

The exam room is where you can continue educating as well as having conversations. Use a technology solution here that features 3D anatomicals and other visual examples of cancer conditions. In a recent survey with OnePoll, we found that 59% of Americans wanted their physician to give them more educational materials on their symptoms.1

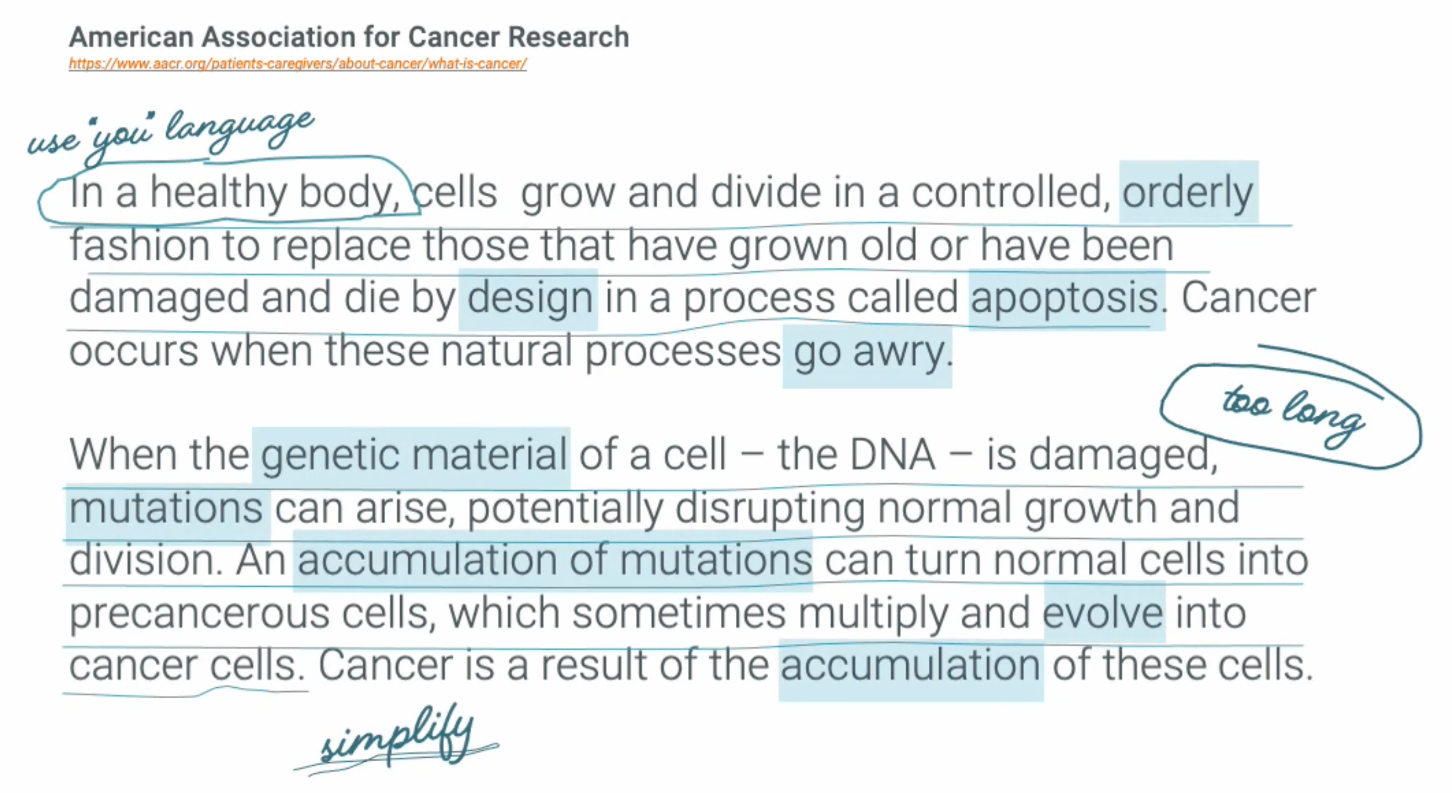

Technology can facilitate your conversations with patients, but it’s also important to use simple language when explaining diagnoses and treatments. 69% of respondents worried their physician would use terminology that they wouldn’t understand.1 That’s why it’s a good idea to avoid medical terminology that patients wouldn’t necessarily know so you can offer the best patient experience.

Screen for SDOH

According to 93% of physician respondents in a BMJ survey, SDOH significantly affects their patients’ health outcomes. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, given that where someone lives determines the food, water, transportation and healthcare they have access to. What may be surprising, though, is that a study found that SDOH impacts 50% of health outcomes, while clinical care impacts just 20% of health outcomes on average.2 Before you can help patients in need, you must first be able to identify patients’ SDOH.

Make screening for health-related social needs a part of your appointments. This is not only good practice, but it’s starting to become more mandatory and is a part of the new Enhancing Oncology Model. However, it’s not enough to simply collect the data. You must close the loop in connecting patients with resources that improve their health equity. In an interview, Dr. Kashyap Patel, CEO, Carolina Blood and Cancer Care Associates said, “If I identify patients sleeping on the street or in a car because they don’t have a home, then I have a moral imperative, as well as I would say quality imperative, to find a shelter for this patient.”

If you have the ability to, you can implement a new care process to meet the needs of your patient population. For instance, if you see a group of patients who don’t have a reliable mode of transportation, you could offer open-access scheduling, additional office hours or telehealth services. Otherwise, be sure to have a list of organizations or resources on hand that can help patients. Even better is if you can send this information via text or email, rather than via a piece of paper they may lose or throw away.

Learn more about how to provide valuable care to all of your patients in our new e-book, “Embracing Patient-centered Care to Improve Outcomes.”

1Unless otherwise stated, all information was received from a OnePoll study conducted on PatientPoint’s behalf from Sept. 22nd to Sept. 30th, 2022 with 2,005 nationally representative Americans.

2Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, et al. County Health Rankings: Relationships Between Determinant Factors and Health Outcomes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. February 2016; 50(2):129135. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.024